The Legend Continues

As the semester comes to a close, it’s time to leave you all with my final post detailing my work with Dr. Donoghue. It’s been a fascinating few months delving into the world of the Captain Morgan, and his legacy that continues to interest historians hundreds of years after his death. It seems fitting to end this semester by writing about the last years of Morgan’s life, those which proved to be the most problematic for the Captain. In October 1683, reports began to reach London concerning a series of riots that occurred in Jamaica, known as the Point Riots. While not explicitly stating what caused them, the State Papers detail the depositions taken directly following the riots; these depositions would condemn Morgan and lead to his so-called fall from grace with the British government and the Jamaican Assembly. It was recorded that a Mrs. Wellin heard Morgan exclaim “God damn the Assembly” in his drunken state (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies October 1683). In the matter of a few days, Morgan’s character and position as a politician in Jamaica were questioned by members of the assembly, believing he was too “irregular” to continue to serve the government’s best interests. On October 12th, 1683, Morgan was charged with “disorder, passions, and miscarriages at Port Royal on various occasions” and for “countenancing sundry men in disloyalty to the Governor” (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies October 1683). Morgan countered these charges, claiming he was a scapegoat taking the blame for the faults of others. Yet, once it was proved that Mrs. Wellin’s deposition held truth, Sir Henry Morgan was swiftly removed from all commands and government offices. Drunken and disorderly conduct was not uncommon amongst Morgan’s contemporaries in government, but in Morgan’s case it was put to the question as to “whether it be to the King’s services that he be continued in any employment, and carried in the negative”. Morgan had offended King Charles II’s pawns in the Jamaican government (individuals that already disapproved of his conduct), giving them the ammunition they required to remove him from power.

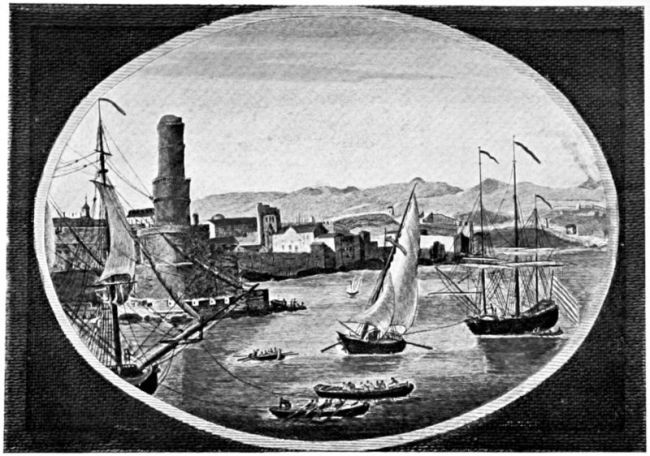

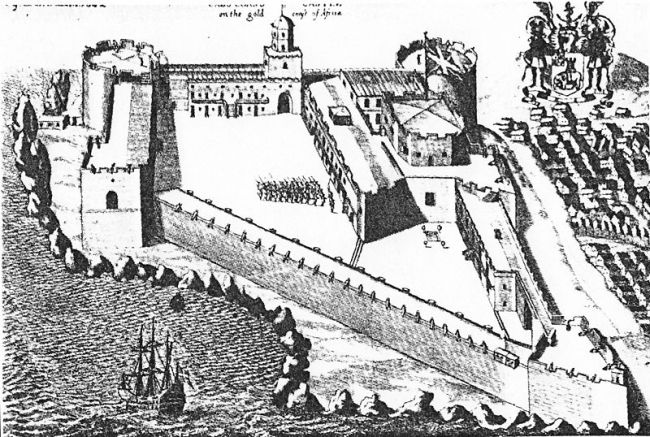

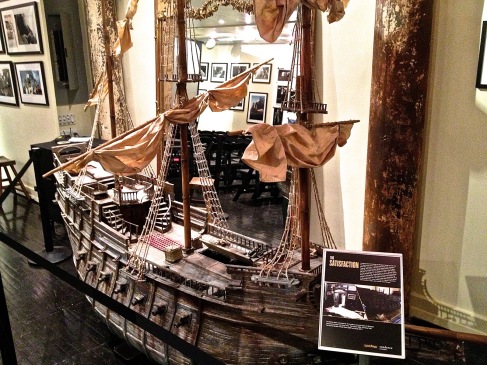

Port Royal, Jamaica

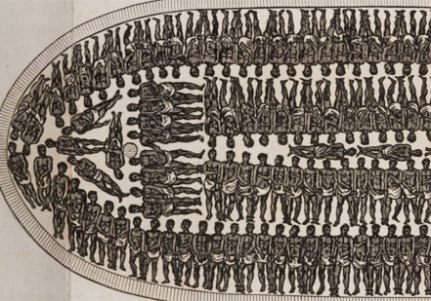

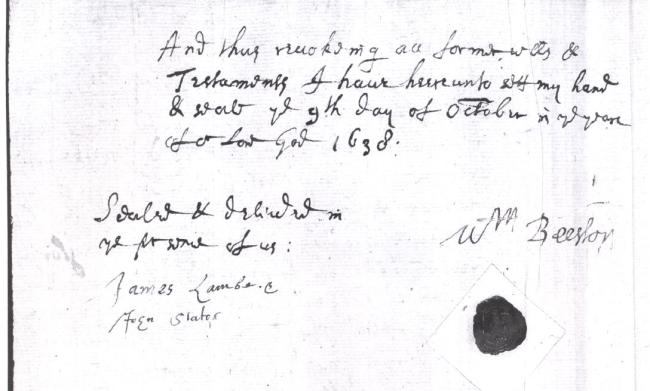

Morgan had distinctly offended Sir Thomas Lynch, one of Charles II’s Jamaican pawns; in 1684, Lynch wrote to Sir Leoline Jenkins, Secretary of State for the Colonies, regarding Morgan’s refusal to pass the recent set of Navigation Acts decreed from England. His concern regarding their passage stemmed from the “drunken little party of Sir Henry Morgan’s” that opposed the new legislation (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America, and West Indies March 1684). Morgan had a history of offending Sir Thomas Lynch, exclaiming on many occasions that he had accepted bribes to support the ineffective Royal African Company in the Jamaican Assembly. Lynch was incredibly critical of Morgan, writing that in his drink he “abuses the Government, swears, damns, and curses most extravagantly, and if you knew all of his excesses and incapacity you would rather wonder why he ever was in employment than why he was turned out” (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America, and West Indies March 1684). It seems that the true piratical spirit never left Morgan when he transitioned to a career of politics, seeking to benefit himself rather than present a cordial attitude towards those he disliked in government. Lynch also claimed that Morgan continually tried to discredit his service as the Governor of Jamaica, supposedly doing so to turn Lynch out of office and become governor himself. Lynch wrote that Henry Morgan was “so uncivil to me, and mightily elated at the prospect of governor” (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America, and West Indies March 1684).

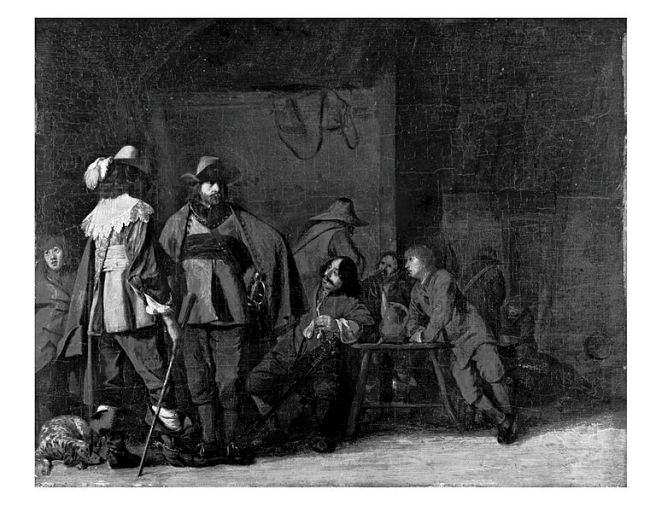

Secretary Leoline Jenkins

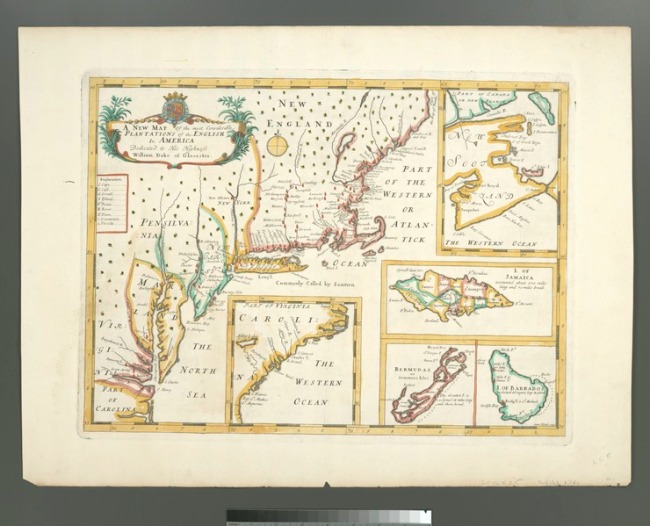

Yet, Henry Morgan was not alone in his fall from grace; his kinsman Charles Morgan, the lawyer Roger Elleston, and Colonel Robert Byndloss were all suspended from their offices in May of 1684. Sir Henry Morgan and Colonel Byndloss were removed from the Jamaican Assembly, while Charles Morgan was dismissed from his offices as Captain of the Forts in Port Royal. In Sir Thomas Lynch’s 1684 letter to Secretary Jenkins, he wrote that both Charles and Henry Morgan lived without “respect to the law, truth, or justice” (Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America, and West Indies March 1684). The actions of these men reached the Lords of Trade and Plantations in London, ordering that Morgan’s petition for their case be formally heard in the council. Although the future seemed bleak for Morgan in 1684, he would later be reinstated to the King’s favor in the last year of his life.

King Charles II

It’s been quite an incredible semester spent researching the illustrious Captain, an adventure which has spanned multiple continents and countless hours of research. While we many never discover the treasure of a simple explanation for the mysteries surrounding his career, it is certain that Captain Henry Morgan’s legacy will continue to live on in the pages of history.